This year I want to spend some time with our roots as United Methodists. I want us as a church to really be able to say that we are laying claim to this thing that sets us apart called Methodism. To do that I want to spend some time this year exploring some of our core beliefs, what it is that sets us apart and gives us our unique identity as Methodists. But I also want to explore our history a little bit, because I don’t think you can easily separate our theology from our history, they inform one another and they shape how we see ourselves today.

For the next few weeks we are going to look a little bit at our history. In order to know where we are going, we need to know where we have come from. We need to remember the values that shaped our movement, so that we can claim those values going forward. Here’s Ashley Boggan talking about this, using the idea of Sankofa.

<video>

So, let’s reach back and reclaim some of our past… because our past can be really powerful.

To start, I want to invite you to Bristol in the year 1739. To give you a picture of the area, Bristol was primarily known for two industries; it was a port city, and by the 1700s it was a coal city. In the 18th century neither of those industries were what you would call refined. Bristol was a working city, one that many of the more refined clergy didn’t really want to go to.

Reverend George Whitfield (longtime frenemy of John Welsey) had begun preaching in Bristol and he was calling other clergy to that city. John Wesley eventually answered the call. He was not Whitfield’s first choice, John’s brother Charles had that honor. John wasn’t the 2nd choice… or the 3rd choice. John was Whitfield’s fourth choice of preachers to come to Bristol, but he was the first to answer the call.

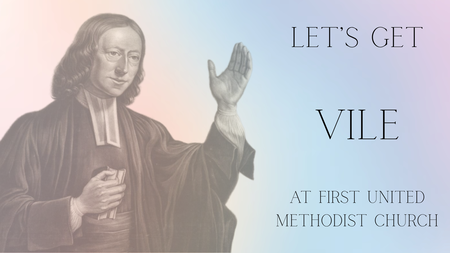

I don’t think John intended to stay long in Bristol. John and Charles were building a movement, and Bristol was not exactly at the center of religious life at the time. When John arrived in the city he found George Whitfield doing something quite scandalous… quite vile in Wesley’s view. Whitfield was preaching in the open air. He didn’t have a church building or even a pulpit, he was just out in the fields preaching to the coal miners and the people of the city.

Something must have struck Wesley in that view of Whitfield preaching to the crowds, because he began to ponder it in his journals. The proper course of action for a member of the clergy was to seek the permission of the local bishop before preaching. Welsey and his fellow Methodists were having a hard time getting that permission, they were seen as quite troublesome in a country that had just spent a good deal of time trying to get rid of religious troublemakers.

On April 2nd pf that year, Wesley makes a statement in his journal that he has submitted to be more vile… that is, like Whitfield, he is going to take up preaching in the fields. I know, doesn’t seem like that big of a deal to most of us. To John Wesley and to most of his contemporaries, this was a big deal. This was his way of going where others wouldn’t and putting aside any thought to what was proper and expected in order to do what was right.

Only problem was, he wasn’t really that good at it. To be fair, John Wesley was not exactly the world’s greatest preacher. Whitfield was a good preacher by all accounts. There are reports of 10,000 people coming to hear Whitfield preach. Even Charles is often said to have been the better preacher between him and his brother. But John brings something to the ministry in Bristol that is powerful, he brings the ability to form communities. If there is an area of ministry that John Wesley excelled at, it was in forming people into communities. He would preach in the fields like Whitfield, vile as it was, but what made his ministry come alive was what happened in these Methodist Societies that he began.

I want to share a story that I didn’t know until a couple of years ago when Ashley Boggan spoke at our Annual Conference in Syracuse. Dr. Boggan has been the General Secretary of Archives and History of the United Methodist Church for the last few years. We have speakers at Annual Conference every year, and they usually speak about something practical, some way that we can bring ministry into our local context. So I was kind of confused as to why we were going to have what appeared to be a history lesson. Not that I was opposed, I love a good walk through Methodist history.

A few years before he went to Bristol, John Wesley was a fellow at Oxford where his brother Charles had started a group of students and faculty who would meet regularly in practice of spiritual disciplines. John kind of takes the group over from his brother (this is a bit of a theme in their lives). This group at Oxford meets regularly and methodically practice things like prayer, fasting, studying scripture, giving alms, caring for the poor… and visiting prisoners. They were often called Bible Moths or Sacramentarians. They called themselves The Holy Club.

As The Holy Club ministered in the local prison they learned of an inmate named Thomas Blair. Blair had been imprisoned for homosexual acts, something that was not only against the law but was punishable by death. Wesley believed that Blair was being victimized by the other inmates and worked to prove his innocence at trial. They failed to prove Blair innocent, but their efforts did help it so Blair was fined rather than executed. Being in prison meant that Blair didn’t really have much money to pay the fine. John Welsey took it upon himself to raise the funds to pay Blair’s fine and get him out of prison.

In a publication describing these events the word Methodist appears for the first time in print. It was not a compliment. Rather the word was used as a pejorative, yet it eventually became the term that Wesley and his followers would be most known by. The story of Thomas Blair is a reminder that at our foundation as Methodists was a willingness to go where others wouldn’t, accept those who others disdained, and a mission to work towards justice in the lives of the downtrodden and oppressed.

A few years later when John Wesley committed to be more vile by preaching in the fields rather than in the churches, it wasn’t that he didn’t want to preach in churches, Wesley very often wasn’t welcome in the churches. Had he asked the Bishop for permission, very likely he would have been sent packing. But that is not to say that Wesley adopted this vile approach out of necessity. Just like with Thomas Blair, Wesley was willing to be seen as vile by his colleagues in order to go where no one else wanted to be – whether that was in prison with a man accused of being homosexual, or amongst the working class of Bristol.

That willingness to go where others won’t, to get involved in the lives that others are ignoring or rejecting, that is built into the core of what it means to be a Methodist. It is quite literally our namesake. And it has the added benefit of being pretty scriptural too.

Our lesson this morning from Luke is all about this idea of being with those that others rejected. In this case it is the tax collectors. Those that proper religious fearing folk thought of as collaborators and sinners. There are writings from religious authorities in Jesus’ day that compare the sins of the tax collectors to murders and robbers. They are the wrong kind of people to hang out with. Yet Jesus makes the choice to do what is vile in the eyes of the powerful, in order to be with the people that he had come to save.

What a powerful image this is. Those who have been rejected are now being welcomed, not just as recipients of the message of Christ – notice this – they are being welcomed as followers, as Disciples of Christ. Jesus doesn’t come saying that being a tax collector is incompatible with the work of God. Jesus doesn’t come saying that there is some lesser role for tax collectors to play in the work that is being done. Jesus invites himself into Levi’s life and brings him into the fold as a Disciple of Christ.

And we heard from the Acts of the Apostles too this morning. Paul spends three of four weeks with the people of Thessalonica, talking to them about Christ, even though he knows that there are plenty in that city who are threatened by his ministry and want nothing to do with him or the Good News that he is bringing. You may even say that Paul was being quite vile in what he was doing.

A willingness to be vile is at the core of our identity. And John Wesley wasn’t even the first Wesley to embrace this vile identity. That honor would probably go to his mother Susanna. Susanna started a ministry in her home, after being displeased with the sermons of the pastor who was filling in for her husband while he was in London. Many locals began showing up to these services Susanna was leading… which also meant that many people stopped going to the services at the local church. As you might imagine she got into a little trouble over this… but I also wonder if this is what sparked John’s willingness to be a bit of a troublemaker by seeing the needs of those around him and putting himself in a position to address those needs even if it meant being seen as vile by others.

And in our early days Methodists were vile in some amazing ways. In the 1700s Methodists were radical; they opposed slavery on principle and required slave owners to free their slaves before joining a Methodist Society. They licensed women to preach. They worked amongst the poor and the sick. They valued a robust education for everyone. These 18th-century Methodist were out to change the world. By the end of John’s life, he ended up doing the most vile thing of all. He started the process by which Methodist would separate from the Church of England. Seeing the need for priests in the recently freed colonies in America, Welsey began ordaining his own clergy to serve where the church refused to go.

Our beginnings are vile.

But our history is not. Next week we’re going to be talking about how a desire for acceptance and conformity crushes that vile spirit of the 1700s, and how Methodism becomes a proper and accessible denomination at the expense of our vile nature.